Do this one thing: Nothing

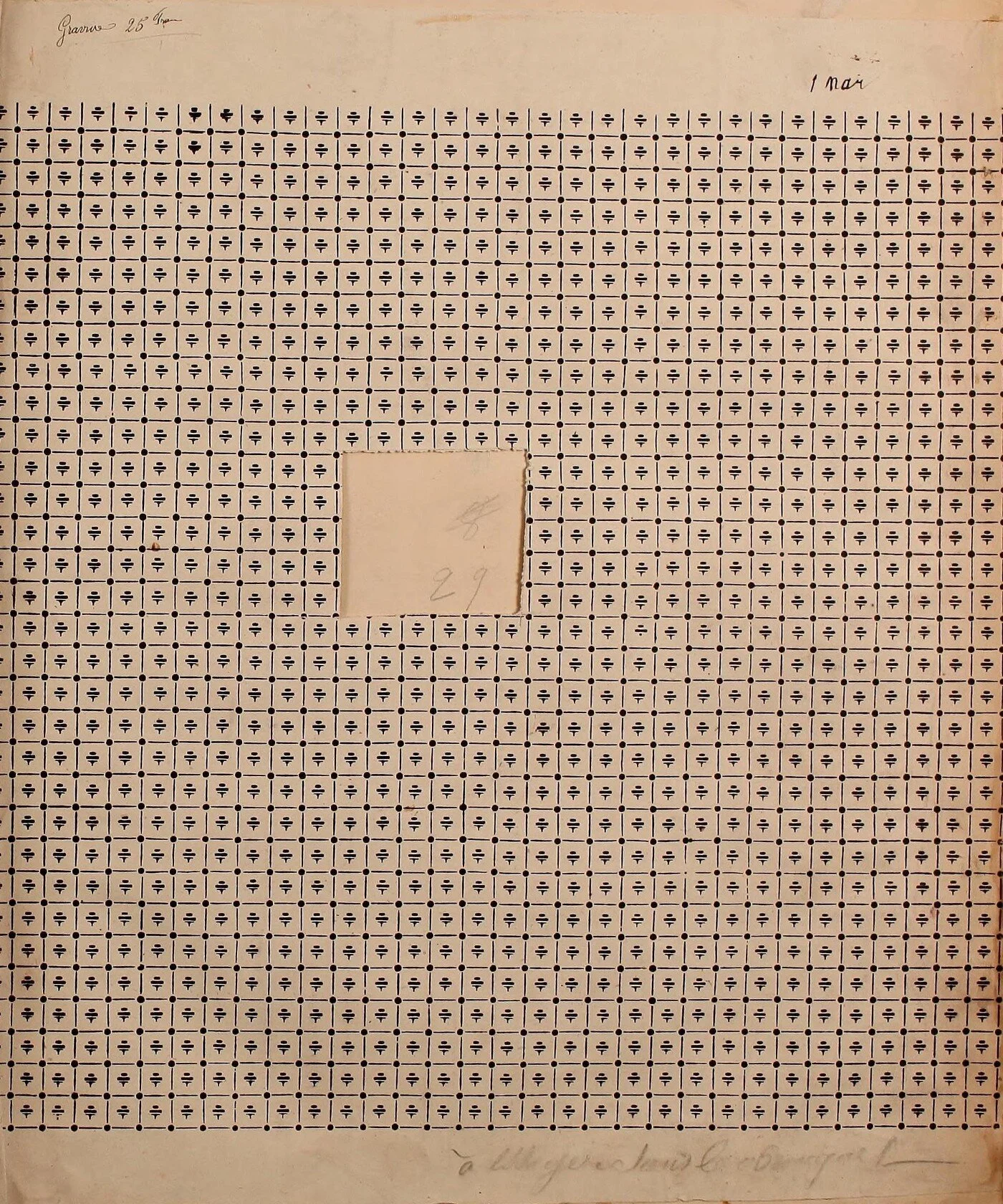

Detail of a textile sample book (1863). Maison Robert, Victor Ducroquet, Paris.

In a world and era where all things must have a function and where “purpose” is sometimes treated as mere buzzword, our ability to dwell in useless activities is vanishing.

Productivity hacks, the “getting-things-done” doctrine, and corporate jargon in general have flooded our waking minds and time. Even our leisure time. How many of us plan our vacation to the last detail, using a sophisticated template or app? How many of us try to read as many books as we can, as quickly as we can? When has reading fast become preferable to reading well?

Why does our time off have to be measured, controlled, or gamified? Isn’t that an absurd paradox: to put restraints on our free time?

Recently, during a no-kids weekend, I caught myself alone while my wife was on her morning walk. I contemplated the Alentejo plane, struggling with the decision about what to do next. My idleness was becoming unbearable. Why was doing nothing so difficult? I started to scrutinize this sensation. Here’s what I came up with, starting with the word “nothing.”

To us humans, "nothing" usually means something, and we have evidence coming to us from the world of physics that supports this idea. It is also easy for us to see "nothing" as the opposite of everything, but this adds little to our understanding. Ultimately, nothing can be anything. Another use for "nothing" arises when we want to categorize an effort or situation of little importance: "it was nothing," we say. In all cases, it is wonderful how generically we can understand ourselves in relation to "nothing" with little effort.

“- O que se passa, querida/o?

- Nada!”

You just know that that “nothing” means something, anything, or even everything.

Let us now explore the idea of "doing nothing." The act of "doing nothing" is actually doing something. It is certainly not the same as "doing nothing." It is precisely when we have nothing to do that anything and everything is possible. Moreover, the verb "to do" is present, indicating some action, some desire or some intention.

In this world obsessed with “doing,” where recognition and legitimacy seem to be attained only by explicit action, doing nothing doesn’t solve the difficulty like the one I encountered having nothing on my to-do list. On the contrary, it may deepen the gap between what we’re “supposed” to be doing and what may arise from some kind of void.

What if we eliminate the verb “doing” and replaced it with “being” or “staying”? Try to stay still, to be quiet or idle, for instance. What happens when you make that decision? Several authors throughout history, from Robert Louis Stevenson to John Cleese, have praised the benefits of idleness and its link to creativity. Sure, it can bring uneasiness or even suffering but if that’s the case with you, you can thereby get a good dose of self-knowledge about your relation to “doing.” Like most things, if one practices staying still enough, one can start to become comfortable with this state.

What I know is that if I didn’t stop and listen to the discomfort I felt that Sunday morning, if I didn’t pay attention to my obsession with finding something to do, these words would not exist.

Originally published in the Journal of Beautiful Business for the "Do This One Thing" series.

Referenced in the article "Is Now a Good Time to Do Nothing?" by Tim Leberecht in Psychology Today .

Inspired by the text "Do nothing", "do nothing" or "not doing"? The words that don't let us be still, by the same author.