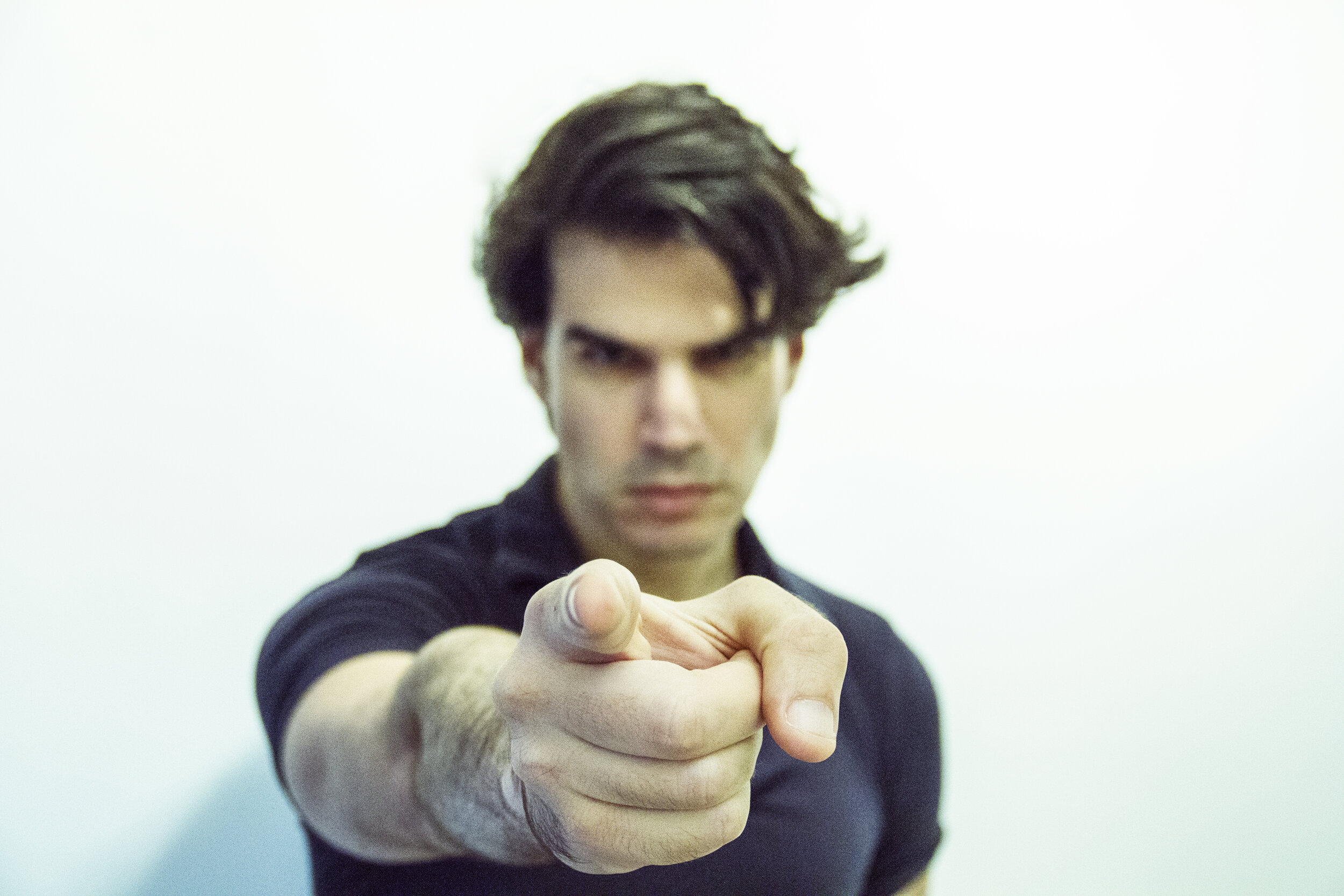

The Accusers - a contemporary portrait

The war context of today's conversations

(...)

Feeling guilty or not. I think it all comes down to this. Life is a fight of everyone against everyone. It is known. But how does this fight take place in a more or less civilised society? People cannot throw themselves at each other as soon as they see each other. Instead, they try to cast the opprobrium of guilt on the other. The one who manages to make the other guilty wins. The one who confesses his mistake will lose. You walk down the street, immersed in your thoughts. Walking towards you, a girl, as if alone in the world, without looking left or right, advances straight ahead. You elbow each other. And here is the moment of truth. Who is going to insult the other, and who is going to apologise? It's a model situation: in reality, each one of you is both the offender and the offender. However, there are those who immediately, spontaneously, see themselves as the tormentors, in other words, as guilty. And there are others who always see themselves immediately, spontaneously, as the one being harassed, that is, in their right, ready to accuse the other and to make him/her be punished. In this situation, would you apologise or accuse?I would certainly apologise.

Ah, poor you, you too belong to the army of excuses. You think you can flatter others with your excuses.

Exactly.

And you're wrong. He who apologises pleads guilty. And if you plead guilty, you encourage the other to continue to revile you, to denounce you publicly, until your death. Those are the fatal consequences of the first apology".

(...)

The accusers and the excusers

It was Milan Kundera (2014), in his work Feast of Insignificance, who wrote the above passage. The accusers Kundera talks about tend to be people who are more certain than doubtful. By not questioning themselves about their responsibility and guilt, they accuse readily. They blame and blame something or someone for their misfortunes and discomfort. Interestingly, the same certainties lead accusers to take credit, completely and utterly, for their victories and achievements. They are certain of others' defeats and their victories, therefore. It seems easy to live like that.

On the other hand, the excusers appear to have a symbiotic relationship with the permanent doubt: "was it me who bumped into you?" To their misfortune, the repeated doubt progressively turns into certainty: "it was certainly me. It was me, as usual".

Kundera makes it clear that some create, nurture and legitimise others. I agree. However, contrary to what the novel seems to make clear, I don't think the solution is to join one of the two armies. Some virtue must be found between these extremes.

Today's society and culture are prolific in creating accusers. It seems that, increasingly, we are no longer tolerating doubt and uncertainty. We need to have everything clear, always. Only then will we be recognised and rewarded, one would think. When the inability to question oneself prevails, "the other" appears, always ready to take the blame and the errors.

The mechanisms are there, in our sight and in our hands; more specifically on our thumbs. For example, social networks and the algorithms that feed their feeds lead us to see more, or only and only, information in line with our interests and points of view. So the networks and other information vehicles reinforce our certainties, with our consent. Moreover, they require us to choose who and what to "follow". Of course, we tend to follow what interests us, what is similar, close to us and does not challenge our opinions. We are contributing to the enlargement of a prison where we are already trapped 1. For me, the worst of prisons is the one that does not look like one and that makes us want to remain trapped.

Added to this dynamic is the quantity and speed of information flow, combined with personal, professional and family demands, in some cases. As we read in the work In the Swarm by Byung-Chul Han (2016), referring to the Information Fatigue Syndrome, "the excess of information leads to atrophy of thought". This syndrome is characterised by the paralysis of analytical capacity, "which makes us capable of thinking", the philosopher explains. It is not difficult to conceive that, for these reasons, we are less able to think about our own ideas. It is more difficult to question ourselves. As a result, it is easier and more likely to attack ideas that are different from our own. And "after a certain point, information ceases to inform and becomes distorted, in the same way that communication ceases to communicate and simply accumulates".

Another sign of these growing incapacities can be seen in the way we offend. Offending has gone from acute to chronic. It is no longer a reaction to something that hurts us or affects our reputation. We are reactive to anything that is dissonant to us; anything that is different simply backfires. As we are all increasingly accusatory the room for excuse is limited.

Conversation as construction or as war

In the golden age of conversation2, conversation was an art, and good conversationalists were craftsmen. Topics such as politics and religion were avoided or were approached with special care. Conversation, from what we read in the manuals of etiquette and good manners of the time, was regarded as a place of learning and where respect was not only practised but also cultivated. Patience, respect for time, for protagonism and for the ideas of others were virtues turned into behaviour.

It is interesting to note that today much has changed in this respect. On television, there is a proliferation of debate (conversation?) programmes about football, which today has as much or more "media weight" than religion had a century or two ago. The same is true of political debate and commentary. In both types of programme the conversation is very different from that which we get from descriptions of what went on in Parisian salons, in the mansions of British nobles, and in the cafés of European capitals where conversations and tertulias took place. Overlapping, attacking, distorting, often overstepping the boundary of good manners. The aim is to win. It only counts if you defeat your opponent, tarnishing his image, if you have the opportunity to do so, by tinting his ideas through manipulation. All this is very different from what was intended of conversation in the old days. Before, learning, building and evolving were the goals of conversation. In fact, a conversation to be good could have no goal except to make the conversation itself rich. And that meant that all who participated in it could come out richer.

When everyone seeks to enrich everyone else, not by force, there are no more adversaries. Perhaps the solution lies in something close to the exercise to which an historian dedicates himself 3. Those who study history seek to get closer to the ideas, intentions and feelings of the people of the past. Because of the distance imposed by time, the object of study of historians is necessarily different from their own. The effort needed to understand and accept that people who lived before us thought differently may help to train and strengthen the "muscles" of tolerance and acceptance of difference. On the other hand, they may help to make rigid and immovable certainties and convictions more flexible.

Maybe we all need to read a little more about history. Maybe we need to invest more energy in asking more questions. Maybe we have to spend less time always having ready answers, in the form of accusations. Not least because, as Maurice Blanchot tells us: "the answer is the disgrace of the question".

Written for Link to Leaders on 18 February 2019; published 27 February 2019