Towards a new definition of work

I posed the following situation during a learning experience I recently conducted for a group of people in an organisation I work with:

"Imagine you walk into a workspace where there is a team of 6 people. It's a team like any other, during normal working hours. One of the members is answering e-mails in a composed way; another person is having a phone conversation, which we can tell is with a client, where the gestures, the tone of voice and the expression show enthusiasm and security; there is another member who prepares materials in piles in a meticulous and methodical way; another two are having a lively conversation, although one can notice some care not to disturb the others, around post-its and documents; the last one is sitting, slightly away from the table, and one notices that he is alternating his gaze in an unpredictable and apparently illogical way between an open book and the window in front of him".

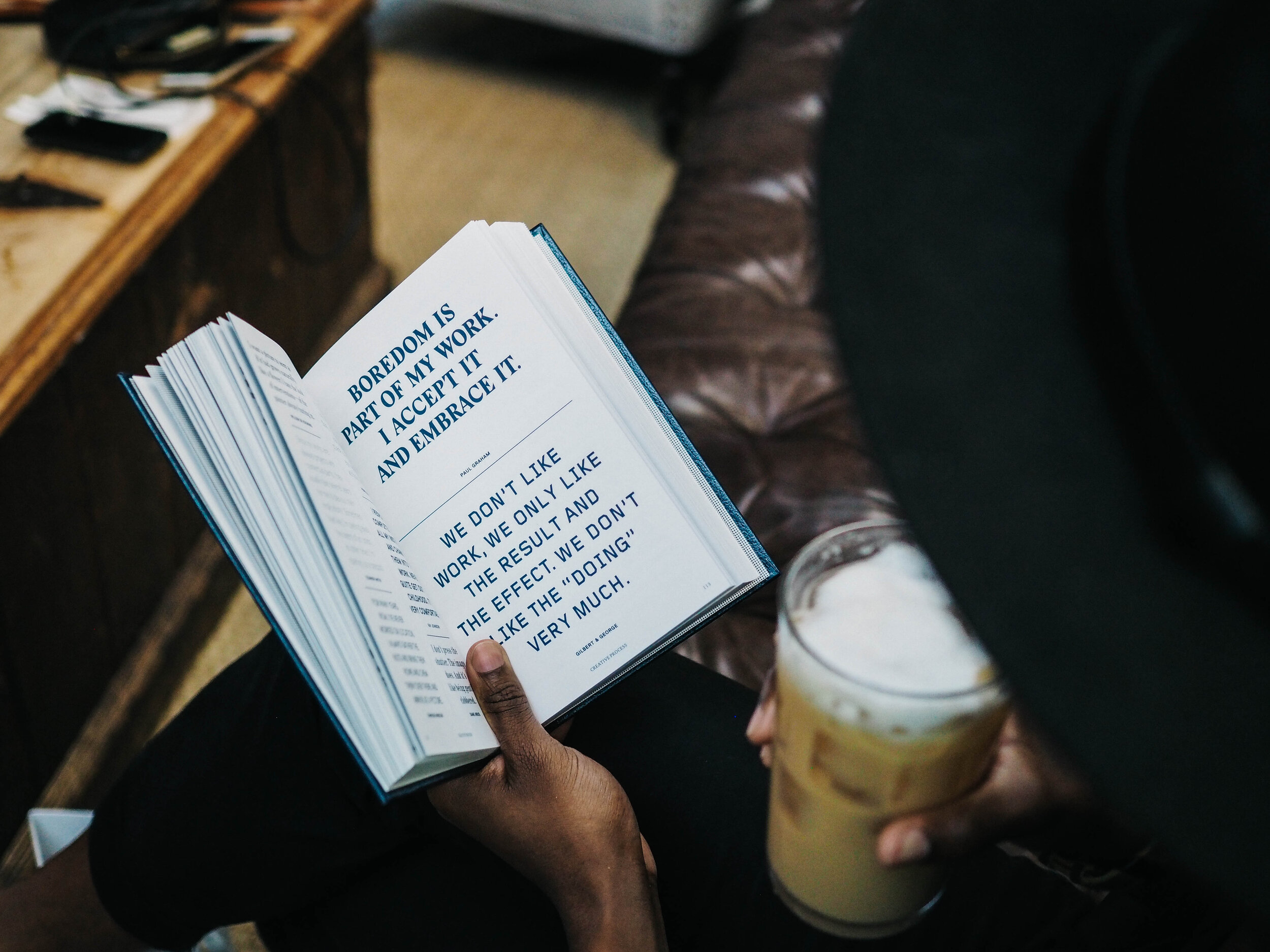

At the end I asked them to share with me and others what they had found in that description. The answers I heard were both amusing and enlightening, regarding the common preconceptions about "work". I heard expressions like: "it's the usual, some working and others looking at the ceiling"; "the one reading this must have been the boss", said another person; "or the boss's son!", added a colleague, making the whole group laugh even more. At a time when much of the work is considered "intellectual work", we are (apparently) paradoxically quick to consider that a person who is reading is not working, producing, making things.

I believe we urgently need to update the existing preconceptions around the world of work, especially at a time when so much is being said about innovation, creativity and 'work-life' balance, probably because there are associated needs. It is curious that this updating exercise does not require much theorising. It is not common for philosophy or arts to be associated to the evolution of the "epistemology of work" but in those fields there are already very interesting and rich proposals that awaken us to the importance of considering other perspectives and giving value to activities that today have little or none.

Business" has been looking for more support and rationale in science and in a more quantitative dimension. Examples of this are the contributions of neuroscience or big data as a basis for decision making, for the implementation of practices and organisational policies linked to the development of people and the business itself. On the other hand, we already notice some penetration of areas considered alternative to the usual ones in the world of work, such as the practice of meditation or design thinking, with apparently good results, from the perspective of users and their employers. However, I have felt and observed that these practices have been adapted to serve the current paradigm without the intention of contributing in a sufficiently present way to change it.

Hanna Arendt, in her work "The Human Condition", Joseph Pieper in his essay "Leisure as the basis of culture", Robert Louis Stevenson with his "Apology for leisure", Paul Lafarge in "The right to laziness", are just a few who, in different times and in different ways, alert to the importance of contemplation, of time spent reflecting on experiences as a basis for creation and creativity, as opposed to the obsession acted with the aim of producing, whatever it may be, effectively and efficiently.

John Cleese, the well-known member of Monty Python, in his autobiography simplifies, as good humorists do, and tells us that human beings function in two basic registers: the "open mode" and the "closed mode". The first is the one that allows us to do things, that occupies us with the list of tasks we have to complete, for example; the second, at one extreme, can mean indulging in boredom and indulgently "doing nothing". According to Cleese, this mode is where new ideas emerge; it is where the potential for creativity lies.

In the modern world of work and, I dare say, in today's society, it is necessary to make room and respect time for leisure, in order to develop business; it is necessary to allow and embrace boredom, strengthening the muscle that resists the temptation to be permanently occupied or entertained; it is necessary to recover the original notions of leisure and contemplation (which over time have become laden with negative meanings and senses) as the basis of human learning and development.

The great challenge is to see that none of this is the opposite of productivity, effectiveness or efficiency. However, it will also be necessary to review these concepts, to modernise them and adapt them to what we have realised does not work today. A paradigm shift in the world of work will imply, I suspect, a change of perspective towards ourselves as working men and women. We need to move beyond the identification and development of skills (whether "soft" or "hard") and look, for example, at something like the virtues pointed out by Aristotle: it will be useful to move from valuing skills to developing certain human qualities.

In order for work to liberate us, we have to free ourselves from a notion of work that has imprisoned us. It is a worn-out version that is out of step with present-day human needs.

“A devoção perpétua ao que um homem considera o seu trabalho só pode ser sustentado negligenciando todas as outras coisas.”

Written for Link to Leaders on 2 October 2017.